In 2009, Venus febriculosa, a blog run by John Bertram, held a book cover competition, asking entrants to redesign Vladimir Nabokov’s classic novel Lolita. Now, Bertram is publishing an entire book of new covers for the novel, each contributed by a prominent designer. Bertram told Imprint that the idea for the contest came after stumbling across Nabokov scholar and translator Dieter E. Zimmer’s gallery of Lolita covers and realizing that they were, well, pretty bad. The contest was marginally successfully, and John Bertram adds:

I sought out well-known designers and artists who I thought would be able to embrace the challenge.

At the same time, I sensed that Nabokov scholars had their own important contributions to make toward such a study and envisioned a multidisciplinary project of images and texts that addressed what such a cover means. I was especially anxious that Lolita herself not get lost in the shuffle, so I sought advice and recommendations from Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, co-founder of the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles, and currently director of graduate studies in graphic design at the Yale School of Art. I am delighted that Sian Cook and Teal Triggs, co-founders of the Women’s Design + Research Unit, agreed to be involved as well as Ellen Pifer, whose essays about Lolita are constant reminders that at the heart of the novel is an innocent abused child. At one point I entertained the notion of only having contributions by women, but, as it is, nearly two-thirds of the covers and half of the essays are by women.

A selection of final designs are below:

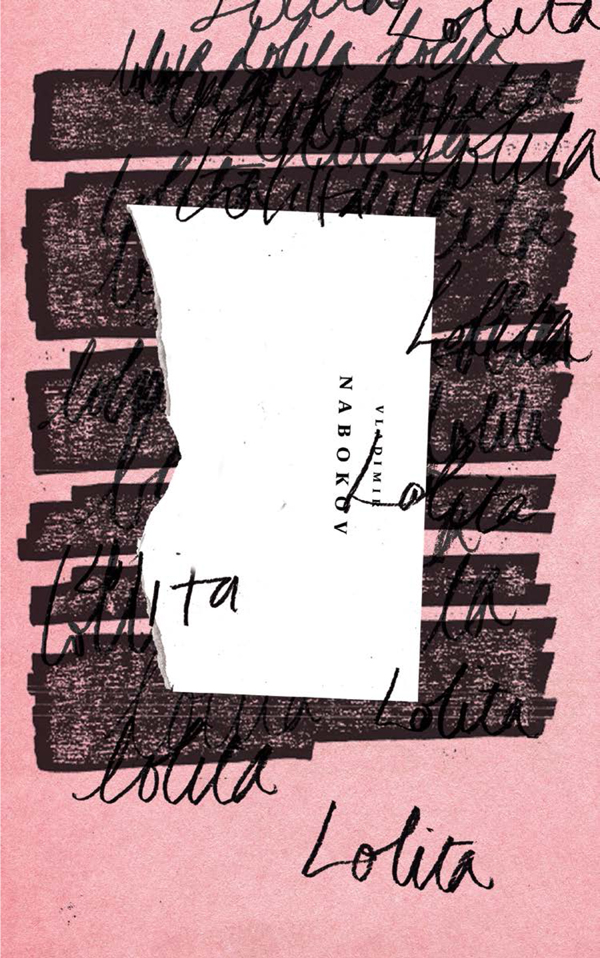

But my favorite design is the one below by Peter Mendesulnd. I think it evokes the “tip of the tongue” phenomenon that Nabokov wants the reader to feel as you read the first sentence (“Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta.):

The version of Lolita that I own is this one (Megan Wilson for the Vintage edition), and I think it’s a great cover. But certainly, I’d love to see any of the designs featured above on my bookshelf.

###

If this topic fascinates you, then check out the following resources:

1) “Recovering Lolita” at Imprint Mag.

2) Jacket Mechanical’s two posts on book cover redesign of Lolita.

3) A Flickr set of more than 160 redesigns of the Lolita cover.